Why is Antony Flewʼs “Conversion to Deism” News, but the testimonies of scholars (and entire seminaries) that left behind formerly conservative Bible beliefs, not news?

by Edward T. Babinski

The media has been making a hubbub about philosophy professor Antony Flewʼs “conversion from atheism to Deism.” However the media has ignored the testimonies of many scholars who during their college careers moved away from formerly held conservative religious beliefs, even though the latter has been known to occur with regularity, which is why conservative Bible believers fear sending their children to most institutions of higher learning, preferring a “Bible college.” However, even sending oneʼs children to “Bible schools” their entire lives is no guarantee they will resist the pull of higher learning and the increasing doubts that entails. The bravest “Bible believing” children with a deep interest in theology and history are often not content to simply preach to the choir at their own “Bible college,” but also seek to obtain higher degrees at the most prestigious institutions outside the fold, because their curiosity is wider than that of most, and they also seek the most direct contact with the best and brightest “non-believers” to listen to what they have to say, and also perhaps to seek to play a role in trying to convert their professors back to “Bible belief” as they understand it. However, what often happens in such cases is the opposite—the views of the formerly conservative Christian student grow more moderate or even liberal, sometimes even atheistic.

In the book I edited, Leaving the Fold: Testimonies of Former Fundamentalists (Prometheus Books, 2003, paperback) there are over three dozen first-hand testimonies of people who left fundamentalist Christianity for either more moderate or more liberal pastures, including a few who left Christianity for non-Christian spiritualities, became agnostics, or even atheists. Some of them left the conservative fold during their pursuit of higher education, though they began their scholarly careers at conservative Bible believing institutions. And not just Bible believing individuals, but entire Bible believing institutions grow more moderate over time with such regularity that all of the most conservative Christian universities were founded in recent times. Over time even the most conservative Christian universities continue to grow more moderate, more liberal. Calvinʼs college that he founded in Geneva was being run by devil-denying Deists two hundred years after he had founded it. Harvard was founded as a conservative Bible believing seminary, and then Yale had to be founded due to the growing “theological excesses” of Harvard. Machen left Princeton Theological Seminary to found Westminster Theological Seminary in 1929 in reaction to Princetonʼs hiring “modernist” professors during the “fundamentalist-modernist” controversy of the early 1900s—a major controversy that split many denominations in America. But today even some sterling graduates of Machenʼs Westminster Theological Seminary like Paul Seely, whose articles are published in Westminster Theological Seminary Review, argues that the Bible spoke of the earth as flat; the tower of Babel story was a myth; and the earth is just as old as modern geologists have concluded. Wheaton College (Billy Grahamʼs alma mater) no longer demands that all of its professors agree that Adam and Eveʼs bodies were created directly from the earth. And Dallas Theological Seminary even has a graduate student whose thesis is that the numbers of the Hebrews who escaped Egypt, as given in the Bible in several places, must be appreciably downsized. Furman University, which was founded by a former president of the South Carolina Southern Baptist Convention, obtained the right to choose its own board members rather than having the Southern Baptist Convention have the last word, and is today a self-governing liberal arts institution.

In conclusion, if the lone conversion of one philosophy professor merely to “Deism” (still far from “Bible Belief” and further still from “inerrancy”) is the greatest “victory” that religious conservatives can muster, it would seem that the Religious Rightʼs campaign to change the minds of the most well educated people in the nation is one of the most absolute and utter failures in human history. The new TV show on the PAX network, “Faith Under Fire,” hosted by Lee Strobel and his Bible inerrantist friends is another such failure. Is he hoping that the intellectuals and scholars he interviews are going to break down on national TV merely after being pummeled by “proof texts” from the Bible? Does Strobel imagine that the inerrantist scholars from various “Bible Colleges” whom he and his producers pick to defend conservative “Bible belief” have studied matters more deeply than the vast army of moderate and liberal scholars around the world? Does he imagine that there truly is no intellectual room for doubting an inerrantist approach toward the Bible? Maybe Strobel will one day obtain enough knowledge of the Bible and its history to begin to recognize where all the doubts lay. The alternative of course is for Strobel to found his own new young “inerrantist Bible believing” institution of learning (theyʼre all young institutions and are born out of the realization that the vast majority of attempts to convert the most intelligent people at long-lived institutions—where the brightest and the best knock elbows—are consistent failures). Though of course in a couple hundred years I bet even Strobelʼs institution would have grown more moderate. I donʼt even need to claim to be an inerrant supernatural prophet to make such a prediction either.

The End

Related Items Below

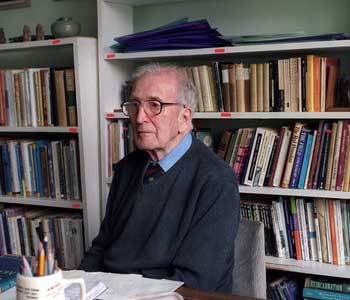

Former conservative born again Christian, Bill Rowe (William L. Rowe), now a well published and kindly atheist professor

Purdue philosophy professor a gentle atheist

In a nation in which 80 to 90 percent of adults say they believe in God, the label “atheist” rarely lands quietly in a conversation.

Say it, and many folks picture some joyless, nasty-tempered misfit who spends his days filing lawsuits against public displays of crosses and menorahs.

What to do then with the gentle, civilized, dog-loving human being that is Bill Rowe?

“Iʼve always been soft about religion in spite of my…” Rowe searched for the perfect word then just smiled. “Thatʼs why I say Iʼm a friendly atheist.”

No one who knows him begs to differ, especially Roweʼs theistic colleagues in the Department of Philosophy at Purdue University, from which he soon will retire. Nor would disagreement come from thousands of philosophy of religion students (I among them) whom Rowe has taught during his 43-year career in West Lafayette.

The author of five books and editor of two more, Rowe will be honored this weekend during a three-day conference at Purdue on the “Problem of Evil.” He and his philosophy colleagues will address the thorny issue of reconciling the existence of an all-powerful, all-loving supreme being with the unrelenting existence of evil and suffering in the world.

“Iʼm just going to give a brief paper trying—once again—expressing this view that the evils in the world count against the existence of God,” Rowe said during an interview in his seventh-floor, Beering Hall office.

“Thatʼs an old argument of mine, and there are some really good criticisms of it that I need to take into account. But Iʼve got some ways of supplementing the argument that I hope will shore it up—at least in the eyes of the faithful.”

If any of that sounds simplistic—We believe in God or donʼt, right?—it isnʼt. As F. Scott Fitzgerald said about the very rich, philosophers are different from you and me. Nothing about their thought processes is a simple stroll from Point A to Point B.

When philosophers “argue” about the existence of anything, especially God, it doesnʼt look like a dinner table fight or a “Crossfire” exchange. There is no yelling or brandishing of Bibles. Often there isnʼt any speech at all because philosophers argue on paper a lot more than in person. Rowe himself is the author of nearly 100 major papers, book chapters, encyclopedia or dictionary entries and reviews. The titles of his papers range from the very big picture—“God and Evil” and “Death and Transcendence”—to the super-specific—“The Fatalism of ‘Diordorus Cronus’” and “Evil and the Theistic Hypothesis: A Response to Wykstra.” In a similar vein, it would be a mistake to assume that Roweʼs arguments for the non-existence of God are the product of an unexamined spiritual path.

Schooled as a boy on Sundays in a variety of Protestant denominations, Rowe experienced an Evangelical conversion in a Baptist church when he was a teenager. For college, he chose the Detroit Bible Institute, with plans to enter Christian ministry.

He transferred after his second year to Wayne State University because his favorite teacher at Detroit was dismissed from the faculty for something called “ultra-dispensationalism.” (Space prohibits even a cursory definition of the term here but, trust me, it isnʼt remotely connected to a disbelief in God.)

At Wayne State, Rowe took philosophy courses to better study theology. One professor, an atheist from whom he was “oceans apart” on religion, emerged as an intellectual mentor, friend and, eventually, catalyst for change. Roweʼs first choice for graduate school, the conservative Fuller Theological Seminary, could not offer him financial aid, so he settled for a three-year fellowship at the University of Chicago Theological Seminary. The intellectual atmosphere was different from anything heʼd experienced. “It was a seminary that wasnʼt fundamentalist and was very liberal in its thinking,” he said. “So, there, I came to get a kind of critical approach to the Bible, learn something about its origins and also came in contact with theologians that were far distant from fundamentalism. The start of my third year, I could feel inside of me my fundamentalism beginning to crumble and disappear.”

How frightening was that?

“It was scary,” Rowe said. “I sat up late at night wondering what would become of me. I started to read Dostoevsky novels. I didnʼt fall apart, but I was concerned about what I sensed were changes occurring in me that I didnʼt really have full control over.”

Rowe soldiered on, received his divinity degree (summa cum laude) and figured he would continue at Chicago for a doctorate in religion. But his professor pal at Wayne State urged him to pursue his obvious gift for philosophy at the University of Michigan. Rowe changed cities and life courses.

During his first teaching stint at the University of Illinois, Rowe attended a theology lecture series and met Calvin Schrag, who was on his way to becoming one of the two pillars of Purdueʼs young philosophy department: When Rowe moved his wife and children to West Lafayette in 1962 to teach philosophy of religion, the second pillar was in place. Last autumn in Philosophy Now magazine, Rowe said his unlikely route to atheism was a gradual and very personal process, not the result of philosophical or scientific arguments contradictory of his theistic beliefs.

Studying the factual origins of the Bible had made him skeptical of its divine authenticity, but the truly compelling factor “was the lack of experiences and evidence sufficient to sustain my religious life and my religious convictions.”

“I knew that it was wrong and arrogant to ask for some special sign from God. But I longed for a sense of Godʼs presence in my life,” Rowe told interviewer Nick Trakakis. “And although I spent hours in prayer and thirsted after some dim assurance that God was present, I never had any such experience.”

“I tried to be a better person and to follow whatever I could glean from the Bible as a life service to God. But in the end, I had no more sense of the presence of God than I had before my conversion experience. So, it was the absence of religious experiences of the appropriate kind that, as I would put it now, left me free to seriously explore the grounds for disbelief.”

During our discussion in his office, Rowe described the longing for a sense of Godʼs presence in the life of another theologian and philosopher, the 11th-century archbishop of Canterbury, St. Anselm. Like Rowe, Anselm was a gifted and lucid writer.

In a nutshell (which is the worst place to put any philosophical premise but all that a daily newspaper has), Anselmʼs famed ontological argument for Godʼs existence goes like this:

God exists because the very idea of a greatest possible being — what the saint called “that than which nothing greater can be thought” — exists, even in the mind of a disbelieving fool.

“Itʼs a very powerful argument,” said Rowe. “Anselm precedes that argument, however, with a kind of lament. Here he is, a Christian saint in charge of monks, and they respect him, love him, and yet his lament is that heʼs never seen God. Heʼs never had what he would be able to say is a personal experience of God himself. And thatʼs remarkable.

“In its place he has to put this argument, a wonderful argument, and itʼs not easy to tear it apart. But itʼs a long way away from a direct personal experience of God.”

Opening his studentsʼ minds to Anselmʼs argument, to the arguments against Anselmʼs argument and to scores of other arguments from centuries of great religion philosophers, is something Rowe has enjoyed since Eisenhower was in the White House. As much as he looks forward to retirement in June, he seems about as burned out on teaching as Warren Buffett is on making money. The predominance of Evangelical religions in America, he said, tends to produce high-school graduates unfamiliar with critical thinking about religion.

“So when they come to university and take a course in philosophy of religion, itʼs a new experience for them to first even realize that there are important arguments, philosophical arguments for the existence of God and to see that what theyʼve accepted on faith can have some basis in reason,” he said.

Likewise, it is a new experience for students to learn in the very same class that “there are not insignificant reasons to think perhaps God doesnʼt exist.”

After he retires, Rowe will continue reading and writing about lifeʼs Big Questions, travel with his wife, Margaret, who is Purdueʼs vice provost of academic affairs, and lavish affection on his 105-pound Labrador retriever, Cody.

“I love dogs,” Rowe said.

When I pointed out that “dog” is “god” spelled backward, Rowe laughed, more like a merry little boy than one of the most important philosophers in America. His delight made me think of a survey result Iʼd recently read: According to a poll by ChristianWebSite.com, 44 percent of U.S. adults believe that “good atheists” will make it into heaven.

Stephanie Salter can be reached at (812) 231-4229 or stephanie.salter@tribstar.com

Endnote: The Society of Christian Philosophers has published a debate book: Contemporary Debate in the Philosophy of Religion Section III. features debates between Christian/theistic philosophers on questions such as “Can Only One Religion Be True?” “Does God Take Risks in Governing the World?” “Does God Respond to Petitionary Prayer?” “Is Eternal Damnation Compatible with the Christian Concept of God?” “Is Morality Based on Godʼs Commands?” “Should a Christian Be a Mind-Body Dualist?” Concerning such questions, none of the Christian/theistic philosophers were convinced by the othersʼ arguments.

Additional First-Rate Scholarly Minds That Left Conservative Christianity Behind For More Moderate To Liberal Pastures

William G. Dever was the son of a fundamentalist preacher. After starting his education at a small Christian liberal arts college in Tennessee (Bob Jones Univ. presumably) he went to a Protestant theological seminary that exposed him to critical study of the Bible, a study that at first he resisted. In 1960 it was on to Harvard and a doctorate in Biblical theology. For thirty-five years he worked as an archaeologist, excavating in the Near East, and he is now professor of Near Eastern archaeology and anthropology at the University of Arizona. In his book, What Did the Bible Writers Know and When Did They Know It?, he writes, “While the Hebrew Bible in its present, heavily edited form cannot be taken at face value as history in the modern sense, it nevertheless contains much history.” He adds: “After a century of exhaustive investigation, all respectable archaeologists have given up hope of recovering any context that would make Abraham, Isaac, or Jacob credible ‘historical figures.’” He writes of archaeological investigations of Moses and the Exodus as having been “discarded as a fruitless pursuit.”

He says what really undercuts the biblical story of the Exodus is the lack of evidence to support what is called “the conquest theory,” that the Israelites took the land of Canaan by force. “There just isnʼt any evidence of widespread destructions of Canaanite cities at the end of the Bronze Age around 1200. And it now appears that most of the early Israelite villages that we have, some 300 or so, are in the central hill country, which had been sparsely occupied before. And these new sites are not established on the ruins of old Canaanite towns, but are established on bedrock or virgin soil. So most mainstream scholars and all archaeologists today would regard these hill country settlers, or Israelites probably, as coming from somewhere within Canaan itself.”

He is not saying that the Biblical Moses was entirely mythical, though he does admit that “.the overwhelming archaeological evidence today of largely indigenous origins for early Israel leaves no room for an exodus from Egypt or a 40-year pilgrimage through the Sinai wilderness. A Moses-like figure may have existed somewhere in southern Transjordan in the mid-late13th century B.C., where many scholars think the Biblical traditions concerning the god Yahweh arose. But archaeology can do nothing to confirm such a figure as a historical personage, much less prove that he was the founder of later Israelite region.”

About Leviticus and Numbers he writes that these are “clearly additions to the ‘pre-history’ by very late Priestly editorial hands, preoccupied with notions of ritual purity, themes of the ‘promised land,’ and other literary motifs that most modern readers will scarcely find edifying much less historical.” Dever writes that “the whole ‘Exodus-Conquest’ cycle of stories must now be set aside as largely mythical, but in the proper sense of the term ‘myth’: perhaps ‘historical fiction,’ but tales told primarily to validate religious beliefs.”

Deverʼs conclusions about what archaeology tells us about the Bible are not very pleasing to fundamentalists or conservative Evangelicals, and I gather that Dever and his colleagues of high standing likewise dismiss fundamentalists and hard-core conservative Evangelicals who want to consider themselves scholars without accepting that which good scholars must do: engage in extensive critical analysis. Those testifying for Deverʼs book (on the back cover) are: Paul D. Hanson, Professor of Divinity and Old Testament at Harvard University; David Noel Freedman, Professor Emeritus of Biblical Studies at the University of Michigan; Philip M. King, Professor at Boston College and author of Jeremiah; William W. Hallo, Professor of Assyriology and Babylonian Literature at Yale University; and Bernhard W. Anderson, Professor of Old Testament, Boston University and Professor Emeritus at Princeton Theological Seminary. Like Dever, these are not a bunch of radical revisionists, but moderates in the field of Christian archeology.

Deverʼs latest book is, Who Were the Early Israelites and Where Did They Come From? Conservative and fundamentalist Christians who interpret the Bible literally will gain no encouragement after reading it.

Bart D. Ehrman apparently started out as a conservative Christian, graduating magna cum laude with a B.A. from Wheaton College, Illinois (a major Evangelical Christian institution from which Billy Graham had also graduated) before attending Princeton Seminary and obtaining his doctorate. His highly successful introduction to the New Testament, The New Testament: A Historical Introduction to the Early Christian Writings (Oxford Univ. Press) is now in its third edition—“It approaches the New Testament from a consistently historical and comparative perspective, emphasizing the rich diversity of the earliest Christian literature. Rather than shying away from the critical problems presented by these books, Ehrman addresses the historical and literary challenges they pose and shows why scholars continue to argue over such significant issues as how the books of the New Testament came into being, what they mean, how they relate to contemporary Christian and non-Christian literature, and how they came to be collected into a canon of Scripture.” Dr. Ehrmanʼs University Lectures are also sold by The Teaching Company that features tapes and CDs.

ETB (April 7, 2005)

No comments:

Post a Comment